By Petra Page-Mann

(inspired by ongoing conversations with Matthew Goldfarb among many other curious humxns*)

When people ask if we have children, we say, ‘yes, and great-great-great grandchildren! And they grow us more than we grow them.’

Most sincerely, these seeds are our family.

Now in our 11th growing season as Fruition Seeds, we also ‘jest’ that we’re an 11th generation farm as we center each generation of tomato, tithonia and turnip.

No joke, though: Seeds have existed 400 million years before us and may well outlive our species by at least that much. Who is growing whom? How? And why?

Change is the Only Constant

Generations of seeds, like generations of humxns, inherit bodies and behaviors both similar to their predecessors as well as adaptive and divergent. Perhaps you can relate: I am remarkably similar to my parents in many ways and utterly unique in a thousand other ways…!

Let’s consider: Given the slight and not so slight shifts inevitable in each generation, consider how the Brandywine tomato we savor today has transformed beyond what was beloved centuries ago.

Indeed, this broad, adaptive diversity is the foundation of life on earth – resilience itself – though celebrating this diversity is something that modernity has thoroughly weeded out of our food system.

In the rush to make an increasingly industrial world both efficient and profitable, vegetables were developed to grow as uniformly as the machines that planted, harvested and shipped them.

Countless generations and cultures have observed that we are what we eat and Friends, this ‘improvement’ of vegetables parallels a very unsettling trajectory in our humxn lives, as well.

There is so much beyond the surface of every seed we sow and root we harvest. These Snow in Tokyo v.1 turnips are helping us explore flavor as well as genetic and cultural diversity beyond Hakurei.

I’ll never forget the day when, deciding which sunflowers’ seed would be saved and why, a dear friend gave me a sideways glance: “Is this eugenics?”

What is Eugenics?

Literally translating to ‘good creation’ in Latin, ‘eugenics’ as a term was coined in 1883 by Sir Francis Galton (cousin to Sir Chales Darwin, clearly inspired though profoundly misinterpreting Darwin’s observations) as the practice or advocacy of ‘improving the human species and reducing suffering’ by ‘breeding out’ disease, disability & other ‘undesirable’ traits. These notions of ‘improvement’ and uniformity deeply resonated with the increasing industrialization of agriculture, strongly influencing plant breeding and many other genetics-based modernist sciences developing in the late 1800s and early 1900s.

Let’s step back for a moment: the ‘perfection’ of the human race has deep roots in western culture. In 400 BC, Plato purported in The Republic that a ‘superior society could be created’ through his ‘mating rules.’ These included ‘rules’ we follow today, such as parents and children best not procreate. Other ‘rules,’ however, cause us to shrink in horror: brothers and sisters may procreate — if they are of high enough class.

Fast-forward: Who, in the language of Darwin, decides whom in humxn culture is ‘fittest’?

Darwin’s cousin and fellow British elite, Sir Francis Galton, deemed mental illness, criminality and poverty both less ‘fit’ as well as genetically heritable. Though his ideas never took off in England, the United States welcomed his thoughts with wide open arms.

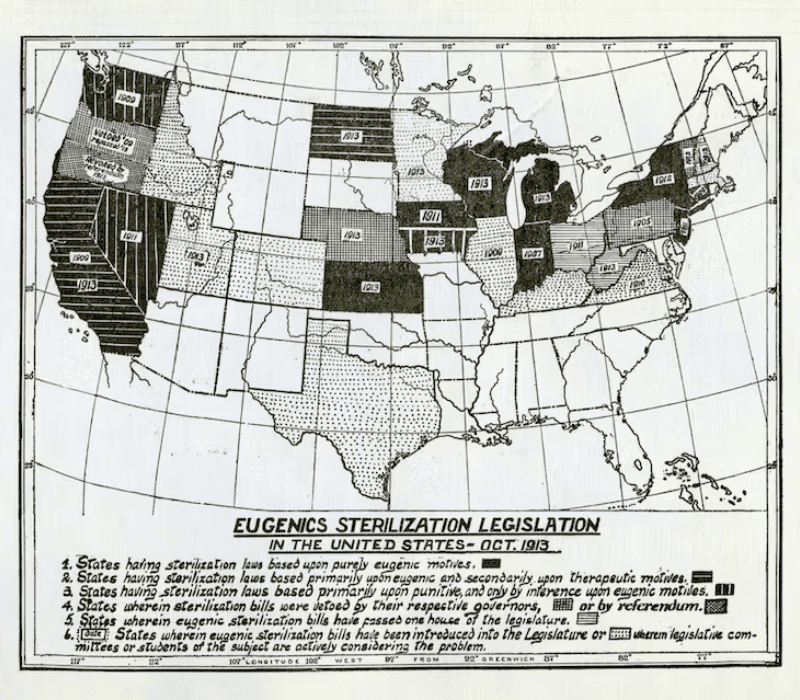

In 1896, it became illegal in Connecticut for epileptics and anyone ‘mentally ill’ to bear children. In 1903, the American Breeders Association was born and by 1911, John Henry Kellogg (yes, the industrialist perhaps best known for breakfast cereal) founded the ‘Race Betterment Foundation’ establishing ‘Pedigree Registration’ to track wealthy families as well as immigrant, minority and impoverished communities. National conferences celebrating eugenics were held throughout the 1910s and 1920s. In 1927 US Supreme Court ruled many ‘negative traits’ such as criminality were caused by ‘bad genes’ rather than racism, economics or social views.

Consensual and non-consensual sterilizations were both common and heralded in the US a century ago and continued as recently as 2010 in California where they were defended as ‘cost-saving measures.’ Credit: University of Michigan.

Indeed, eugenics bloomed in the United States even past World War II, when Hitler brought to vivid life the implications of ‘human betterment.’

As countless organizers before us have observed:

Oppressions Don’t End, They Evolve

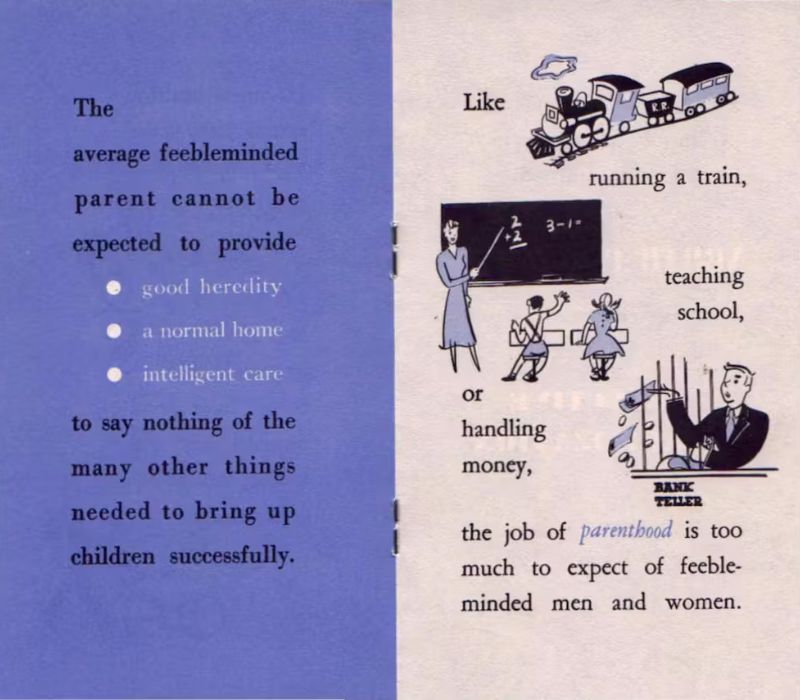

We’ve been humbled and horrified learning more about the extent of these insidious histories. The state-run “North Carolina Eugenics Board” operated until the mid 1970s. Even more recently, between 1997 and 2010, approximately 1,400 forced sterilizations were performed on women in California prisons, deliberately targeting populations considered ‘less worthy of reproduction and family formation.’ The doctor performing the sterilizations told a reporter the operations were ‘cost-saving measures.’

A pamphlet extolling the benefit of selective sterilization published by the Human Betterment League of North Carolina, 1950. Caption and photo credit: University of Michigan.

Eugenics persists in countless ways today including anti-trans legislation, cochlear implant pushing and carceral policy as well as in gene editing, both in humxns & vegetables. Even without touching the genome, imagine the uniformity of all the heads of lettuce — and indeed, every vegetable — in a grocery store.

It’s chilling and no surprise hate crimes are at an all-time high: We are what we eat.

Indeed, the parallel histories of humxn and plant ‘improvement’ are not coincidental.

Like uniform vegetables on a supermarket shelf, how have you felt pressure to fit within cultural norms?

The Past: So Present

Let’s step back: From ten thousand years to a century ago, to be a farmer was synonymous with being a seed saver, synonymous in turn with being a plant breeder. As longtime and landrace seedkeeper Joseph Lofthouse loves to remind us: everything we know, love and depend upon in agricultural diversity is the genius vision of indigenous farmers, patient and brilliant, illiterate only by modern standards. Countless generations and entire cultures were plant breeders before DNA was even described.

Today, only a few ‘experts’ decide who is ‘fittest’ and will thus survive both humxn eugenics and plant breeding. Not coincidentally, these faces are often the most ‘superior’ and thus privileged by society. (Indeed, let me here name my own white-skinned, blond presence reflecting the hierarchical supremacy of our time, though presenting as female bucks the trends.)

This concentration of power has both narrowed who becomes and identifies as ‘plant breeder’ as well as who even saves seeds in the United States, with vast implications.

And Friends, before we steamroll professional plant breeders and create new fictions of fracturing hierarchy valorizing indigenous seedkeepers while painting modern, formally trained plant breeders as overprivileged and shortsighted people to distrust solely on the practice of eugenics, let’s step back. Creating black and white narratives of who is more valued — and thus more humxn — falls prey to much of the same logic that reinforces hierarchies perpetuated by the dominance culture that have prioritized industrial over humxn values far too long. Leah Penniman of Soul Fire Farm observes that “demonization is colonization” and in that spirit, we ask:

How do we build deeper relationships, in our communities and with ourselves, so we can hold contradictions as well as accountability in love, dismantling systems of oppression in the world?

We are committed to the intersectional work of cultivating cultures of curiosity, courage, and commitment to change as we seed new possibilities for humxn-plant co-evolution, starting always with ourselves.

As we resist eugenicist tendencies, elevating individual agency around who we ‘reproduce with’ and how — both humxn and plant — is key. In our relationships with plants, this encourages us to question trait uniformity and other symptoms of seed as commodity as well as exclusivity in its practice, celebrating the capacity we all have to save the seeds we choose, according to our own unique needs and dreams. Seed is one of the pillars of sovereignty on every level.

Widening our lens beyond the United States, let’s consider that just as white-supremacist nation-states have historically and continue today to dominate and destroy people and nation-states of color, so too eugenics-based processes of plant breeding today are working through national and international policy to justify the centralized control over plant reproduction. This includes the erosion of deep relationships with seeds, particularly in indigenous communities through policies like UPOV – the International Union for the Protection of New Varieties of Plants — which profoundly controls and privatizes seeds. UPOV imposes intellectual property rights on varieties and allows corporations to monopolize them. Traditional and indigenous seeds are being ‘discovered’ and appropriated by these corporations, restricting their access once a part of their ‘breeding programs.’ Learn more here, including how you can join us resisting UPOV.

Where Do We Go From Here?

Have you ever felt pressure to fit within cultural norms, including those that feel defining and confining of you and people you love?

How do we cultivate connection, community and care after so many generations of domination?

How do we re-imagine and live into the world we dream of?

There are as many ways to move forward as there are seeds, growers and stars in the sky.

As we (un)learn alongside so many plants and humxns, we are leaning more and more towards diversity as we grow, save and share seeds.

With equal parts curiosity, humility and joy, we co-adapt and play with plants, regionally adapting both long-beloved heirlooms and cultivating new ‘heirlooms of tomorrow,’ as K Greene so eloquently says.

Three delectable community favorites helping us explore new turnip expression: Hakurei (left, photo credit Johnny’s Selected Seeds), Scarlet Queen (center, photo credit Johnny’s Selected Seeds), Tokyo Market (right).

Breeding Turnips Beyond Eugenics

If what we tend grows and we reap what we sow, we’d love to share with you our unfolding process of co-adapting alongside Hakurei — one of the most delectable and widely-planted hybrid turnips of all time — as we cultivate deeper diversity in our gardens and beyond.

And Friends, there are endless permutations of plant breeding models. I don’t pretend what I’m about to share with you is novel, innovative or unique. I do offer it as an exciting, imperfect and constantly evolving approach as we deepen our own relationship with and understanding of plants, ourselves and our community.

To start, we’ve never tasted anything like Hakurei: Lusciously sweet with creamy, refreshingly crisp flesh and silk-smooth skin, bright ivory. Hailed as the queen of salad turnips, Hakurei is an F1 Hybrid, so any saved seed will grow not just a little but a lot different from the parent roots. Many white salad turnips exist that are ‘open-pollinated’ and while their seed will grow similar to the parent roots, their flavor and texture is not nearly as sweet and satisfying. Hoping to cultivate an irresistibly scrumptious open-pollinated (OP) salad turnip, we did what we sow often do: We sowed seeds.

After trialing many forms and flavors of both hybrid and OP salad turnips with our community, we planted the three delectable favorites in the fall of 2020 to help us explore new turnip expression. We tucked hundreds of roots into the cellar of Tokyo Market (white OP), Scarlet Queen (red-skin, white flesh F1 hybrid) and Hakurei (white F1 hybrid) – to overwinter and re-plant the following spring.

Cross-pollinating turnips! With Angus, Fruition’s Farm Lead, with plenty of turnip-carrot kraut to share.

In March 2021, we re-planted these roots in two separate high tunnels far enough away from each other — two thousand feet away from each other, with a large barn in between — so their pollen wouldn’t cross. In one tunnel we planted ~300 total roots interplanting Hakurei and Scarlet Queen on one-foot centers; in the other we planted the same amount of roots, interplanting Hakurei and Tokyo Market. We trellis their raucous 4+ foot stalks of brilliant canary yellow flowers smelling like honey and hay, covered in butterflies and bees, harvesting the seed once pods turn from green to gold in mid-July.

The next generation! We dry freshly harvested turnip seeds pods before threshing. And awe: One seed may grow ten thousand.

Here in the Finger Lakes of New York, Zone 5, this leaves plenty of time to plant this seed — the next generation! — to grow and mature roots to overwinter, starting the cycle anew.

In fall of 2021 we witnessed that first cross in our fields, both marvelous and mystifying. As expected, the two white turnips (Hakurei x Tokyo Market) grew beautifully white turnips, vigorous and sweet — not as sweet and smooth as Hakurei, though well on their way. The other cross (Hakurei x Scarlet Queen) grew, predictably, about 75% white roots with the balance being not crimson-skinned like the parent, but brilliant amethyst PURPLE!

The first generation of Hakurei crossed with Scarlet Queen! Is purple?!! Delectable diversity, indeed. We call this ‘Plum in Tokyo’ and this is their v.1 (as in version 1) iteration.

Each purple-skinned root had creamy, sweet white flesh with a starburst of purple in the center. For the extra-seed curious out there: a) we love you and b) we moved forward with seed only harvested from Hakurei, so we could be sure that pigmented roots were in fact natural crosses.

That fall we invited everyone who came to the farm for events and farm tours to see and sample the delicious diversity unfolding before our eyes. As we co-adapt with plants, we love to experience and make decisions in community. The more people actively seeing, tasting and offering insight, the more profoundly adaptive we all are, both plant and humxn.

Excited to share these seeds as well as the story, we filled packets for our community. We named the white turnip ‘Snow in Tokyo’ and the white-purple turnip ‘Plum in Tokyo,’ adding a ‘v.1’ to the end of each name to honor the first ‘version’ or ‘vintage’ of these seeds shared. These turnips are part of our wider See(d)ing the Change project celebrating delicious, adaptive diversity and honoring the unique expressions of each generation, both plant and humxn.

Image 8 caption: We love to share seeds we love with humxns we love! Note the v.1 celebrating the unique expressions in these generations that have never yet existed and will never exist quite the same way again.

From our collective tastings and vision, we again tucked hundreds of roots into the cellar to overwinter, re-planting them in spring 2022. We again planted them in isolated tunnels, trellising their fabulously fragrant flower stalks turning to seed. By late July we were planting the next generation and what we saw next took our breath away.

As hoped, with community selection, the white roots were continuing to sweeten more consistently (joy!) and the delightful surprise came when we noticed rose-pink roots emerging alongside the purple and white roots in the second cross (JOY!). In this next generation, about 50% of the roots were white with the balance being half rose and half purple. Each colorful root had creamy, sweet white flesh with a starburst of corresponding rose or purple in the center. Sharing (and tasting) these roots with our community throughout the fall was a highlight for all.

Stay tuned for these gorgeous Plum in Tokyo v.2 seed to be shared in fall 2023, Friends…

…and if you’d love a witness (and taste!) these turnips on the farm alongside acres of our organic seed crops and See(d)ing the Change projects, join our free field day on Saturday, August 19th between 2 and 4. For full details to this and so many other events, hop on www.fruitionseeds.com.

Look what the next generation of Plum in Tokyo is growing! Hope to see you here on the farm to help us make selections for the future, Friends.

Curiosities Continue

As we pluck purple, pink, and white roots to savor on the grill for supper, we’re questioning our tendency to pick a singular quality to define a variety. We’re also grappling with supremacist thinking that any of these qualities may be better than any other. We continue to struggle as we navigate if and when to remove plants from the field that we perceive as unhealthy, or not vigorous enough. What is adaptive diversity? What is respectful selection? In our gardens, in ourselves, in our communities?

While perhaps the term ‘eugenics’ and its use to justify centralized control over people’s lives and deaths has become less politically acceptable over time, plant breeding has in many ways been a place where the underlying logics that justify that control are harbored. Since the beginning of plant breeding as a modernist science, the field has consistently accepted and reinforced the idea that there is inherent (‘objective’) superiority between different genes, bodies and lives. Behind every vegetable in a supermarket are many plant breeders who have preached the virtues of ‘elite genes’ and ‘superior genetics’ that they have been selecting for — and “roguing out” the inferior.

Friends, as we re-weave ourselves into the family of things (always, Mary Oliver), let’s re-kindle our courage to cultivate communities and cultures of curiosity, care, belonging and delicious, adaptive diversity both in ourselves, in our gardens and in our world.

Let’s dig a little deeper than the thin veneer of modernity’s current uniformity and control: for more than ten thousand years prior, the values of co-adaptive, delicious diversity were at the center. Though direct lines to this lineage may have been severed, the deep resilience inherent in the fact of each seed — and each of us — is irrefutable. Together, let’s lean in. Let’s remember. Let’s re-imagine.

As we go, here are a few

Reflection Questions to Accompany Us:

~ What have we learned from society about diversity, both in plants and in people? When is it acceptable to celebrate diversity? When not? How do economic systems influence this dance? How does this play out in the seeds we sow?

~ In the language of Darwin, revisited: How do we make ourselves ‘fit’ so we survive our times? What did we learn about as children to ‘fit in’? How have we adapted our ‘adult’ lives to survive? Where and with whom — humxn and beyond — do we not only survive, but thrive? What if survival of the ‘fittest’ is survival of the kindest, most curious and compassionate?

~ Is there a seed, food and / or cultural tradition that connects you to a time before (or beyond!) modern eugenics? How might you deepen this tradition and welcome others to grow with you?

We’re here to be grown by (and share!) the seeds growing us and thanks for joining us on the journey, Friends.

We are the seeds.

Sow Seeds & Sing Songs,

*Humxn is a gender neutral term expanding the masculine histories of ‘human.’

What a beautifully written essay. Thank you for such thought-provoking ideas. While I decry the size and uniformity (and blandness) of commercial produce I had never thought of it in quite these terms. An example: the last 2 years my raspberries have struggled due to drought, heat and grasshoppers. The berries I pick are often small and not always “pretty”, but oh so flavorful. Last week my boyfriend brought me a carton of commercial raspberries: thumb-sized, perfectly shaped and colored, and almost tasteless. I’m trying to teach him the difference between my home-grown garden delights and commercial produce. Maybe when we share the first Ambrosia corn from my garden it will drive home this message. I can’t wait to try your gorgeous turnips next year!

I love your emails. Always informative and inspiring. Thank you Petra and the Fruition crew.